May: Bánh Bột Lọc

I start this blog entry with a heavy heart. It has been three weeks since the murder of George Floyd, and I feel I have been despondent since.

I have seen many friends speak on the importance of the Black Lives Matter and End Police Brutality movements eloquently, and thus, I’d rather yield the time that you might dedicate to learning more about how to support these movements to folks of color who speak on this matter through experience and with clarity. Friends who are looking for more resources on how to process what’s happening, I have two recommendations:

I eased out of the funk this weekend because I was recently reminded by a friend, who was explaining my blog to her husband, that my work is a culturally-sustaining practice. Reflecting upon this statement, I have come to view the act of upholding my heritage and my identity in dominant White culture as a liberatory act, and I embrace the time you are committing to learning about me and my culture as an act of understanding who I am as a Vietnamese-American. (Thank you, W., for reminding me about my purpose!)

I am also going to remind myself as I type that, while I am not expecting to be perfect when I cook these meals, I will hold myself to a similar expectation when it comes to blogging. Thus, I have relieved Andrew of his typical responsibility of revising and editing this particular post. (He is more than happy to reclaim this extra time to commit to his own personal projects.)

What do bánh bột lọc mean to me? Why bánh bột lọc?

I grew up loving bánh bột lọc (or, as I will call it for those who can’t hear and see my pronunciation of the name, BBL) and all of its properties: its uniqueness, clearness, chewiness, starchiness. Imagine clear tapioca dumplings the size of your palm with deliciously seasoned pork and shrimp on the inside, lounging in a pool of spicy fish sauce and green onions. Or, you don’t have to imagine it as much as look at this picture.

I remember feeling like BBL was so special because I did not see anyone make it like my mom did. Restaurants usually serve them in tubular formation, wrapped in banana leaves, or as tapioca balls that were half the size and half the tastiness. I recall biting into store-bought BBL and being disappointed because the shrimp skin was intact, or frozen shrimp was used instead, or the pork piece was more fat than meat.

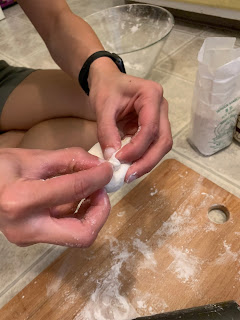

Nothing matched the preparation and presentation of my mom’s BBL. I recall my mom would alternate between sautéing the pork and shrimp and preparing the tapioca dough. (No one can multitask like my mom.) Thảo and I were often invited to help her with making the Vietnamese dumplings, which was the penultimate step to the completion of this treat. Mom would have us seated on the floor around the chopping board. She then would pluck a small portion of the large tapioca dough, cover it back up with a moistened towel, use a rolling pin to flatten out the ball, and would hand over the dough to Thảo or I to stuff with the cooked pork and shrimp filling. Thảo and I would close the dough like a taco, and pinch around the edges together to seal the deal. We would laugh as we set down the pre-cooked BBL on a tray, comparing our pinch-and-fold methods and the beauty marks that eventually appeared: the stuffing would sometimes poke a hole through a vulnerable spot in the BBL, leaving an oily, red-orange hole for my mom to cover with leftover dough.

Much like the chả giò process, BBL requires an all-hands-on-deck approach. Thus, when my sister told me that she and her partner, Skye, wanted to visit us, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to make this cooking project happen.

How did I make bánh bột lọc?

Linked is a Google Document with my mother’s recipe. To process the recipe, I annotated it with thoughts about how I could make the prep easier. I also had the opportunity to talk out the process with my mom as I prepped the ingredients; it was nice to hear her reflect on how important this dish is to central Vietnamese folks. (I’d like to think that I am thicker than your average Vietnamese gal because I was raised on central Vietnamese cuisine, which is typically more carb-forward and more flavorful.)

Thảo and Skye are amazing photojournalists, so I will be sharing this process via the photos they took.

|

| I embraced my mother's approach of working from the floor. |

|

| I attempted to walk Thảo, Andrew, and Skye through a model of how to make BBL. |

|

| I can't remember: Was it just pinch, or pinch-and-fold? Let's just say that Thảo, per usual, rocked the folding contest. |

|

| A+ for effort! |

|

| The crew post BBL-folding! |

|

| A tray of pork&shrimp BBL, and a tray of fake meat&shrimp BBL. Can you guess who prepared which tray? |

|

| There's always time for an Eggsy break. |

|

| The Nguyễn sisters together again! |

|

| Me hydrating and admiring Thảo's work with lathering the BBL in oil and green onions. |

|

| The final product, pre-fish sauce. |

|

| An indulgent breakfast the morning after. |

Who tried my bánh bột lọc?

Andrew, Thảo, Skye and I enjoyed BBL after five hours of labor in our solarium -- a fancy word a colleague introduced to me to replace the word “shed.”

I made a non-pork version with the intention of sharing it with Antoinnae, so I shared a portion of it with her.

How was it?

I was initially disappointed that the dish was more starchy than it was flavorful. But -- as my mother predicted -- the more the BBL cooled, the more time the flavors had to set in, and the better it tasted. I was overall pleased with my ability to accurately identify a worthy pork substitute for the veggie-shrimp BBL; I used a vegan version chả lụa, which is a steamed pork roll that is typically sliced like lunch meat. While the pork and shrimp BBL almost held a candle to my mother’s BBL, I think the veggie-shrimp one made the product uniquely mine.

Some memories that remain from the experience are the conversations that Thảo and I freely had about the trauma we endured in our childhood. That evening -- and the next morning over breakfast -- Thảo and I embraced storytelling roles as we talked about the ways that our parents handled integrating into the United States as Vietnamese refugees, and the profound impact their actions had on us as their children.

We recalled one story where both of us were “disciplined” because, through our foolish actions, I had gotten locked into our shared bedroom. The events that unfolded after my parents got home and unscrewed the doorknob can go unsaid, but I always remembered that event with great guilt. That, among many of our childhood events, reminded me of the inequity of discipline my sister endured as the eldest child; the pioneer child of two stressed, struggling parents who escaped their home country to guarantee a better future for children they had only idealized and never met. And now that we were a reality come true, we had been interpreted as bratty, ungrateful American children who would never understand the sacrifices that they endured for us.

When we recalled this specific story, I told my sister that I felt horrible about the pain that she endured as the eldest child, and that I empathize with the immense pressure she dealt with in that role. In turn, she empathized with me for having to follow orders when my parents told me to retrieve the “disciplinary” tools on behalf of my parents; she understood that I was damned if I did it, and damned if I didn’t.

When she said that, I felt catharsis that I did not know I needed and wanted. To clarify, my sister and I have a great relationship now, and we have since our early adulthood. But when two siblings grow up together, I think there are phases in our life that we can identify and recognize as one would objectively with historical eras, and there was one era that felt like a dark five-year stage. I always looked back at that childhood era with guilt that I could have done more to support my older sister, to show her that I had her back no matter what. To have her tell me that she understood my actions back then -- it was like I received forgiveness for an unsaid apology.

Comments

Post a Comment